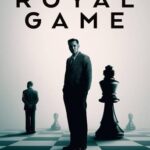

Overview

1938. While the Nazi troops march into Vienna, the lawyer Josef Bartok hastily tries to escape to the USA with his wife but is arrested by the Gestapo. Bartok remains steadfast and refuses to cooperate with the Gestapo that requires confidential information from him. Thrown into solitary confinement, Bartok is psychologically tormented for months and begins to weaken. However, when he steals an old book about chess it sets him on course to overcome the mental suffering inflicted upon him, until it becomes a dangerous obsession.

Introduction to “Chess Story”

“Chess Story” (also known as “The Royal Game” or “Schachnovelle”) stands as a mesmerizing cinematic adaptation that plumbs the depths of human resilience. Released in 2021, this German-Austrian drama masterfully translates Stefan Zweig’s final novella into a visual opus that captivates both chess enthusiasts and casual viewers alike. The film chronicles the harrowing psychological journey of a man who uses chess as his salvation during Nazi imprisonment. Its nuanced approach to mental fortitude amidst political oppression renders it not merely entertainment, but a profound meditation on the human spirit’s indomitable nature. The narrative’s intricate psychological layers unfold like a complex chess strategy, keeping viewers intellectually engaged throughout its runtime.

Stefan Zweig’s Literary Legacy

Stefan Zweig, the Austrian literary virtuoso whose pen crafted “The Royal Game,” remains one of the 20th century’s most translated authors. His oeuvre, characterized by psychological acuity and humanistic values, found its poignant culmination in this novella, completed shortly before his tragic suicide in 1942. Zweig’s perspicacious insights into the human condition permeate the text with an almost prophetic quality. His own exile from Nazi-occupied Europe lends the story an autobiographical resonance that transcends mere fiction. The film honors this literary provenance with meticulous attention to the philosophical undercurrents that made Zweig’s work so enduringly relevant. His legacy of exploring mental resilience against totalitarianism finds perfect expression in this adaptation.

The Film Adaptation: From Page to Screen

The transmutation of Zweig’s cerebral prose to cinematic language presented formidable challenges that director Philipp Stölzl navigated with consummate skill. The screenplay, penned by Eldar Grigorian, distills the novella’s essence while expanding certain elements to exploit the visual medium’s strengths. Stölzl’s directorial choices amplify the claustrophobic ambiance of the protagonist’s incarceration through ingenious camera work and set design.

Plot Synopsis: A Mind Under Siege

The narrative unfolds in 1938 Vienna, following Dr. Josef Bartok, a wealthy lawyer who manages assets for the aristocracy and Catholic Church. As Nazi forces annex Austria, Bartok finds himself arrested by the Gestapo, who demand access to his clients’ accounts. His steadfast refusal results in solitary confinement in a hotel room turned prison cell. The psychological torture inflicted by his captors threatens to unravel his sanity until he serendipitously steals a book of chess grandmaster games. This contraband treasure becomes his lifeline as he mentally plays both sides of each match, creating an alternate reality within his besieged mind.

The Historical Context: Nazi-Occupied Austria

The Anschluss and Its Impact

The film’s historical backdrop—the 1938 Anschluss (annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany)—provides crucial context for the protagonist’s ordeal. This pivotal historical junction marked the systematic dismantling of Austrian independence and the implementation of Nazi ideology across all societal strata. The film depicts this transition with chilling verisimilitude, from swastika-adorned buildings to the palpable atmosphere of suspicion and fear. Director Stölzl recreates this historical milieu with meticulous attention to period details. The Anschluss serves not merely as historical backdrop but as an active antagonistic force, embodying the systemic oppression against which Bartok must deploy his mental chess strategies. Through carefully constructed scenes of Vienna’s transformation, viewers witness the macrocosmic political events that precipitate the protagonist’s microcosmic struggle.

Intellectual Persecution in the Third Reich

The Third Reich’s systematic persecution of intellectuals forms a crucial thematic strand throughout “Chess Story.” The film illustrates how Nazi ideology targeted not only physical resistance but sought to eradicate intellectual autonomy and cultural heritage. Bartok’s imprisonment exemplifies the regime’s fear of independent thought and its determination to subjugate minds as well as territories. The subtle portrayal of how totalitarianism functions through isolation and psychological manipulation gives viewers insight into oft-overlooked aspects of fascist control mechanisms. Chess as a Metaphor

The Duality of the Game

Chess serves as a multifaceted metaphor throughout the film, embodying both salvation and madness for the protagonist. The game’s inherent duality—its simultaneous simplicity of rules and infinite complexity of execution—mirrors Bartok’s psychological state. The black and white squares represent the moral absolutes in conflict during wartime, while the diverse movement patterns of individual pieces reflect the varied strategies of survival in totalitarian regimes. Director Stölzl ingeniously visualizes this duality through contrasting lighting schemes and composition. The film explores how the same mental activity can constitute both an escape from reality and an obsessive prison of its own making. The chessboard becomes a microcosm of the larger political battlefield, with each move carrying existential significance beyond the game itself. This metaphorical richness elevates the film beyond mere historical drama into the realm of philosophical inquiry.

Mental Escape Through Strategy

Bartok’s immersion in chess illustrates the mind’s remarkable capacity to create freedom within confinement. His strategic thinking transcends the immediate circumstances of his imprisonment, establishing an internal domain beyond his captors’ reach. The film depicts this mental escape with ingenious visual techniques—floating chess pieces, superimposed boards, and subtle transitions between reality and imagination. These cinematic devices allow viewers to experience the protagonist’s psychological journey from within. The chess strategies become increasingly complex as Bartok’s mental state evolves, reflecting his growing dissociation from external reality. Yet this escape mechanism carries its own peril, as the boundaries between mental exercise and obsession blur dangerously. The film thus poses profound questions about the nature of freedom itself—can mental liberation compensate for physical incarceration, or does it merely constitute another form of imprisonment? This philosophical tension propels the narrative forward with intellectual urgency.

The Protagonist’s Journey

Dr. Josef Bartok’s Character Analysis

Oliver Masucci delivers a tour de force performance as Dr. Josef Bartok, embodying the character’s transformation from self-assured, affluent lawyer to hollow-eyed prisoner with remarkable subtlety. Bartok’s initial characteristics—dignity, intellectual confidence, and moral rectitude—undergo a gradual metamorphosis through his ordeal. Masucci conveys this evolution through minute changes in posture, vocal inflection, and gaze, creating a psychological portrait of extraordinary depth. The character’s complexity lies in his contradictions: his stubborn defiance coexists with increasing fragility; his intellectual brilliance harbors the seeds of potential madness. The screenplay provides Bartok with a nuanced emotional landscape that transcends simplistic heroic templates. His journey interrogates conventional notions of courage and resistance by demonstrating how survival sometimes necessitates psychological compartmentalization rather than overt defiance. This character study forms the emotional nucleus around which the film’s thematic explorations revolve.

The Psychological Imprisonment

The film excels in depicting psychological imprisonment as equally devastating as physical confinement. Bartok’s luxurious hotel room-turned-cell becomes a mental battleground where silence and isolation function as sophisticated torture mechanisms. The cinematography emphasizes this psychological dimension through claustrophobic framing, distorted perspectives, and temporal discontinuities that mirror the protagonist’s disintegrating sense of reality. Particularly effective are scenes where the room’s dimensions seem to shift according to Bartok’s mental state, creating a visual correlative for his psychological experience. The Gestapo officer Böhm, played with chilling restraint by Albrecht Schuch, epitomizes the insidious nature of psychological warfare through his calculated manipulation rather than crude physical violence. This portrayal of mental imprisonment resonates beyond its historical context, offering insights into contemporary understandings of psychological trauma and resilience. The film thus contributes to broader cultural dialogues about the nature of captivity in its various manifestations.

The Power of Mental Resistance

The film powerfully articulates how mental resistance can constitute a profound form of opposition against oppressive regimes. Bartok’s refusal to surrender information transforms from simple stubbornness into a philosophical stance against totalitarianism. His chess obsession, while ostensibly an escape mechanism, simultaneously represents an assertion of intellectual autonomy that his captors cannot breach.

Visual Storytelling and Cinematography

Thomas W. Kiennast’s cinematography elevates “Chess Story” with its virtuosic visual vocabulary. The camera work juxtaposes expansive, opulent shots of pre-war Vienna with increasingly constricted framing during Bartok’s imprisonment, creating a visual journey that parallels his psychological confinement. Musical Score and Atmosphere

Critical Reception and Awards

The film garnered substantial critical acclaim following its release, with particular praise directed toward Masucci’s commanding central performance and Stölzl’s assured direction. Critics highlighted the film’s successful navigation of the challenges inherent in adapting a primarily internal, psychological narrative to a visual medium. “Chess Story” received numerous accolades at European film festivals, including nominations for Best Feature Film at the German Film Awards and recognition for its technical achievements in cinematography and production design. International critics noted the film’s relevance to contemporary discussions about mental health and political resistance, with several reviews drawing parallels to modern authoritarian tendencies.

Comparative Analysis with the Original Novella

The film adaptation demonstrates both fidelity to Zweig’s novella and strategic divergences that exploit cinema’s unique storytelling capabilities. The core narrative remains intact, but Stölzl expands Bartok’s pre-imprisonment life and post-liberation experiences to provide greater character dimension. This expansion allows for visual establishment of what Zweig conveyed through exposition, creating a more immersive historical context. The novella’s first-person narration finds cinematic translation through occasional voiceover and subjective camera techniques that maintain the original’s psychological intimacy.

Themes Explored

Isolation and Survival

The film meticulously examines isolation as both a weapon of oppression and a catalyst for psychological adaptation. Bartok’s solitary confinement serves as a microcosmic laboratory for exploring how humans respond to extreme isolation, with chess emerging as his particular survival mechanism. The narrative suggests that isolation’s psychological impact can be more devastating than physical torture, gradually eroding one’s sense of reality and self. Director Stölzl visualizes this theme through increasingly abstract representations of time passage and spatial distortion within the hotel room.

The Human Capacity for Adaptation

The film offers a nuanced examination of human adaptability under extreme circumstances, neither romanticizing suffering nor underestimating resilience. Bartok’s psychological evolution throughout his imprisonment demonstrates how the mind develops survival mechanisms that would seem impossible under normal conditions. The narrative presents adaptation as morally neutral—neither heroic nor compromising—but simply as the mind’s natural response to unbearable circumstances.

The Cast’s Performance

The ensemble cast delivers performances of remarkable psychological depth, anchored by Oliver Masucci’s multifaceted portrayal of Josef Bartok. Masucci navigates his character’s transformation with surgical precision, physically embodying the gradual effects of isolation through subtle changes in movement patterns and vocal rhythms. His performance is particularly impressive during the chess sequences, where he convincingly portrays both sides of Bartok’s fractured consciousness with distinct physical and verbal characteristics. Albrecht Schuch creates a memorably understated antagonist as Gestapo officer Böhm, eschewing Nazi caricature in favor of bureaucratic menace—a banality of evil made all the more disturbing by its recognizable humanity.

Director’s Vision and Execution

Philipp Stölzl’s directorial approach balances meticulous historical recreation with innovative psychological visualization. His background in opera direction informs the film’s rhythmic pacing and visual composition, creating a narrative that unfolds with almost musical structure. Stölzl demonstrates particular skill in translating internal mental states into visual language without resorting to heavy-handed symbolism or explanatory dialogue. His collaboration with cinematographer Thomas W. Kiennast yields a visual strategy that evolves alongside the protagonist’s psychological journey, from classical composition in early scenes to increasingly subjective perspectives during imprisonment.

The Cultural Significance of Chess in the Film

Chess functions in the film not merely as plot device but as cultural signifier with rich historical and intellectual associations. The game’s position as an intellectual pursuit transcending national boundaries makes it the perfect symbolic counterpoint to the Nazi ideology that celebrates national and racial divisions. The film thoughtfully explores chess’s paradoxical nature as both a war simulation and a pure intellectual exercise removed from physical violence.

Psychological Elements in “Chess Story”

The film offers a sophisticated psychological study that anticipates many concepts from modern trauma theory and dissociative psychology. Bartok’s mental bifurcation into two chess personalities represents a form of dissociation that functions simultaneously as survival mechanism and psychological threat. The narrative carefully traces the progression from voluntary mental exercise to involuntary psychological fragmentation, illustrating how protective adaptations can become pathological under extreme stress. Particularly insightful is the film’s portrayal of how traumatic experiences persist beyond their immediate circumstances, shown through Bartok’s triggered response to the shipboard chess match.

The Film’s Relevance in Today’s World

Despite its historical setting, “Chess Story” resonates with contemporary concerns about authoritarianism, psychological resilience, and intellectual freedom. The film’s portrayal of how totalitarian systems target not only political opposition but intellectual independence speaks to current debates about information control and thought suppression in various global contexts. Bartok’s experience of isolation acquired unexpected relevance during the COVID-19 pandemic, when global lockdowns prompted renewed interest in the psychological effects of solitary confinement and the mental strategies for enduring isolation.

Similar Films and Recommendations

Viewers captivated by “Chess Story” might appreciate other films exploring psychological resilience under political oppression. Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist” similarly examines survival through artistic engagement during the Nazi era, while “A Beautiful Mind” parallels the theme of genius bordering on psychological fragmentation. For those interested in chess as metaphor, “Searching for Bobby Fischer” and “Queen of Katwe” offer complementary perspectives on the game’s transformative potential. Films like “The Lives of Others” and “Night and Fog” provide additional perspectives on authoritarian control systems and resistance.

Conclusion: The Endgame of “Chess Story”

“Chess Story” culminates not in simplistic triumph but in ambiguous survival—a complex denouement befitting its sophisticated psychological journey. The film’s conclusion suggests that while Bartok has escaped physical imprisonment, his mental liberation remains incomplete, with chess simultaneously representing his salvation and his ongoing psychological entrapment.

To learn more about this remarkable film, visit its IMDb page.